The case for NATURAL FULL OUTER JOIN

In this post, I will try to highlight a very useful SQL technique, based on the quite unfamiliar NATURAL FULL OUTER JOIN. One might think THE FULL OUTER JOIN operator was added to the standard only for symmetry reasons, But when combined with the NATURAL qualifier, this can become a powerful tool in some situations. In the classical SQL JOINs explanations, the FULL OUTER JOIN returns the whole combination of both sets, that is, no rows are discarded.

Table A

| Column1 | Column2 |

|---|---|

| value11 | value21 |

| value12 | value22 |

| value13 | value23 |

Table B

| Column2 | Column3 |

|---|---|

| value22 | value31 |

| value23 | value32 |

| value24 | value33 |

Result

SELECT * FROM tableA FULL OUTER JOIN tableB ON tableA.column2 = tableB.column2

| Column1 | Column2 | Column2 | Column3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| value11 | value21 | value21 | |

| value12 | value22 | value22 | value31 |

| value13 | value23 | value23 | value32 |

| value24 | value24 | value33 |

If we join tables A and B on a specific join condition (for instance A.ID = B.ID), a resulting row will be output in each of the 3 cases :

- For a given row in A, there is one ore many rows in B who match on the join condition -> all selected columns of A and B are output in the resulting row

- there is no match in B for this given row in A on the join condition -> selected columns of A are output and B’s selected columns all receive nulls

- there is no match in A for a given row in B on the join condition -> A’s selected columns all receive nulls and selected columns of B are output

So, in the SQL implementation, contrary to INNER and LEFT joins, we can’t drive the join from an outer table to an inner one : both tables will have necesarilly all their rows considered. Linked to this, it is interesting to note that FULL OUTER JOINs are not currently supported by the H2 database.

Now, the NATURAL keyword. It will allow to ommit the join condition between columns of the two tables. The common column names are used instead, and are all included in the join condition with equijoins.

So, if we arrange to full outer join two tables, and we add for both at least one common column name, which values will always differ between those two tables, we know that no row will be aligned based on common values, like we would get in a classical join. We still get all rows from both tables, but with zero match. So if there is N1 rows in table A and N2 rows in table B, the resulting resultset will have N1 + N2 rows. That is not true for the number of columns though, because we arranged to have at least one common column name (there could be other common columns also), and contrary to the example above without NATURAL, common columns are not duplicated in the result.

Table A

| Column1 | Column2 |

|---|---|

| value11 | valueA |

| value12 | valueA |

| value13 | valueA |

Table B

| Column2 | Column3 |

|---|---|

| valueB | value31 |

| valueB | value32 |

| valueB | value33 |

Result

SELECT * FROM tableA NATURAL FULL OUTER JOIN tableB

Common columns are typically listed first

| Column2 | Column1 | Column3 |

|---|---|---|

| valueA | value11 | |

| valueA | value12 | |

| valueA | value13 | |

| valueB | value31 | |

| valueB | value32 | |

| valueB | value33 |

So what we did here is a special kind of concatenation : not a perfectly aligned one like what we get with UNION ALL.

With this combination appears the use case : to be able to concatenate many resultsets, potentially sharing no common columns except one which will contain a tag differentiating the row types (if this row after join pertain to table A or table B), without being forced to specify a join condition, which could have no meaning in case no common column exist. So in this regard, what is brought by using NATURAL is an easier syntax and being able to avoid to express an intention that doesn’t exist, with a join condition which would thus just be arbitrary. To achieve this concatenation, the full outer join would have been sufficient. But Using NATURAL, we can more easily express a cleaner intention : “I don’t care, there is no join condition between those resultsets, I just want to concatenate them”.

But the most important point is now : why would we want to concatenate two resultsets in this way ? Reasons could be multiple. I will show one possibility : to be able to execute many queries under the same transaction, without requiring to use serializable transaction isolation levels. This leads to some other questions :

- why would we want to execute several queries in a same process like if we were the only user on the database ? Because for instance we could try to execute a query giving an aggregated resultset (using GROUP BY), and also another query giving the corresponding detail data which will be used in drill-downs, in situation where we cannot (or don’t want to) use some adhoc DDL. If we work on a classical datawarehouse, where new data only arrives during night batches, we don’t have to worry about reproducibility of query results executed during day sequentially, separated by intervals of few seconds or minutes. But when we do the same thing on a real-time BI system (because it’s 2019), where inserts or updates can happen (and actually happen) at any time, we cannot get this guarantee. And that indeed becomes a source of small but constant deltas. It can mean also that some test suites never pass to 100%.

- why would we want to avoid using elevated isolation levels to just achieve that ? Because in some cases it is simply not possible. For instance, in Oracle, READ ONLY isolation level is not available via JDBC, and SERIALIZABLE, on frequently updated systems like real-time BI ones, returns most of the time the infamous ORA-08177: can’t serialize access for this transaction, even if touched rows were not directly updated during the serialized transaction (and that is a topic in itself…).

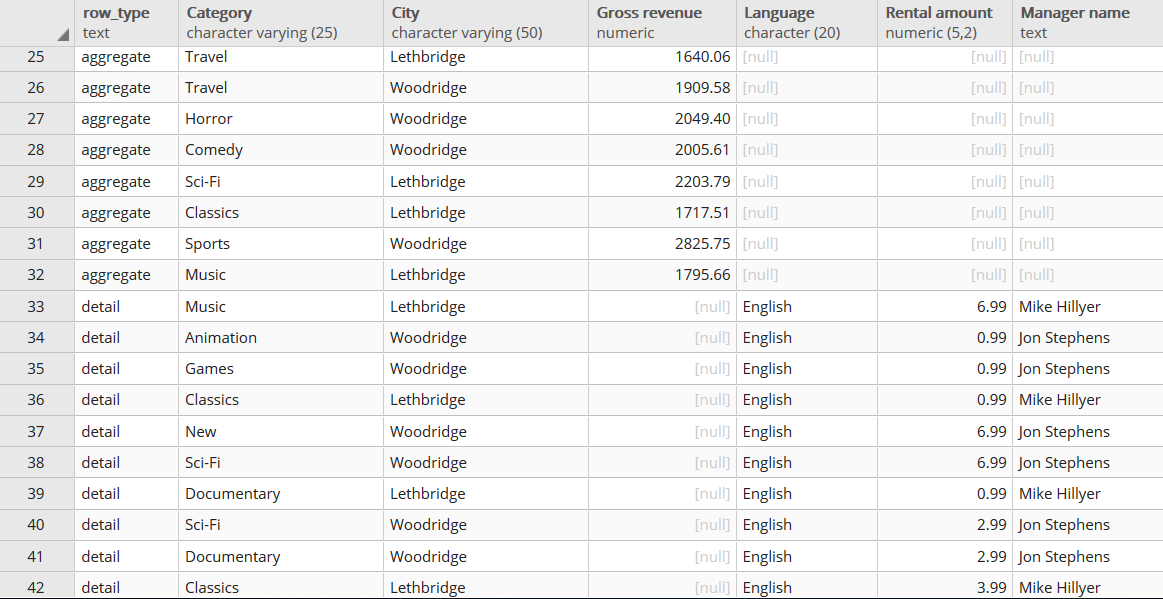

Here I give a small example on postgresql, with sakila schema :

The query concatenates as explained above an aggregated result, to be used in a dashboard (presenting some KPIs), and also the corresponding detail query, giving data that will be used in drill-downs from the same dashboard. The “row_type” column contains two distinct values, and allows to retrieve the two disjoint resultsets. Technically, as explained above, it is this column which prevents both tables to have any matching row.